Integrating Air Support for Faster Resupply and Distribution

Planes, Trains, Automobiles…and Now Helicopters:

Integrating Air Support for Faster Resupply and Distribution

Written by LTC Mikhail “MJ” Jackson and COL Phil Lamb

Foreword

As a career Army Aviator and the current Chief of Staff for America’s First Corps, I can attest, “the enterprise” consistently underutilizes Rotary Wing lift in support of the Sustainment Warfighting Function. Decades of CTC and WFX AAR’s can confirm to include I Corps most recent Warfighter experience.

The Army often becomes infatuated with things that go “boom” and often underplays the importance of the things that protect and sustain the “pointy end of the spear”. In the INDOPACIFIC, Long Range Precision Fires (MDTF) are the current flavor of our lethal effects infatuation. However, where the Army remains truly the foundation of the joint force lies within Sustainment WFF. Especially in LSCO, it is what only we, the Army, can do at sufficient scale and scope.

The INDOPACIFIC operating environment requires robust and redundant multi-modal (air, land & sea) logistics capability/capacity.

MAJ MJ Jackson’s paper creates a demand signal and a glimpse at a roadmap for necessary transformation and evolution. It discusses how we might task organize, measure effectiveness, and potentially deliver combat credibility to the priority theater.

To ensure lethal and survivable formations when crisis turns into conflict, we must get this right. To get this right, we must first maximize the use of CH and UH capacity in training (CTC/WFX) as a leading indicator of true operational readiness across the force in contact.

Introduction

In the military, maneuver units are laser-focused on executing their mission and engaging the enemy, often without fully considering the complexities of supply logistics, which can sometimes be overlooked amid the urgency of operations. Their primary objective is to defeat the enemy, but they rely on timely resupply to ensure mission success. Meanwhile, sustainers are tasked with the intricate responsibility of delivering those supplies efficiently and swiftly to keep the fight going. A systems approach connecting the tactical fight and supply logistics can mitigate reactiveness to resupply amid the urgency of operations. Traditionally, ground transportation has been the primary means of supply delivery, valued for its reliability. However, in today’s dynamic and fast-paced battlefield, one must ask: is ground transportation still the optimal solution? Could there be a more agile and strategic approach to ensuring that maneuver forces receive their supplies faster and more effectively? I argue that there is, and it lies in a more deliberate integration of rotary-wing and fixed-wing air support. In an era where contested logistics is the norm, especially in the vast and austere geography of the INDOPACIFIC, our current reliance on ground-based resupply alone is operationally risky, and tactically insufficient. While fixed-wing support presents challenges requiring joint coordination, rotary-wing assets remain a valuable and controllable resource within the Army’s reach. For sustainers to truly enhance the maneuver fight, we must expand our approach to distribution—leveraging both ground and air assets. This lesson was reinforced through assessments conducted during two recent exercises, proving that success in modern warfare demands a broader perspective on logistical operations.

Enhancing Mission Success through Effective Air Resupply Integration

The use of air support for resupply is not a new concept, but it remains significantly underutilized and often overlooked in supporting mission success. The hesitance to employ air support for sustainment resupply missions can largely be attributed to many sustainers' limited familiarity with rotary and fixed-wing assets, and the perception of limited, lighter loads. Rotary-wing aircraft, in particular, are not commonly within the direct control or capability of sustainers. However, the absence of such assets does not diminish the importance of understanding how to effectively use or coordinate their employment. As sustainers, it is essential to be proficient in a range of resupply methods, particularly those that serve as combat force multipliers. Brigadier General Eric Landry, Deputy Commanding General of Operations for I Corps, emphasizes the importance of adaptable and resilient support systems in his article “Fortifying Operational Readiness in the Pacific”, published in Military Review, noting that “constant movement to evade detection and respond to threats puts persistent strain on logistics and readiness.”[1] Maintaining resupply across vast, contested distances demands flexible and redundant support systems to ensure operational continuity. In this context, air support emerges as a vital enabler, offering faster and more efficient resupply options while minimizing risks to personnel and increasing the likelihood of mission success. A pervasive misconception in resupply operations is the assumption that ground transportation is the sole method of distribution. This approach is often over-relied upon, particularly in environments where terrain conditions make ground transport infeasible. In such situations, alternative distribution methods, including air support, are essential for maintaining operational effectiveness and success. “Air absolutely has to be incorporated into the logistics synchronization matrix, and we as sustainers need to be demanding customers of both rotary and fixed-wing assets,” said MG Gavin Lawrence, Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics and Operations (G-3), U.S. Army Materiel Command (AMC).[2] Similar to MG Lawrence’s perspective, as a logistician, I believe achieving effective sustainment requires leveraging multiple means and modes of transportation—airlift being a critical enabler. Rotary and fixed-wing capabilities must be integrated into the logistics synchronization matrix, and sustainers must take an active role as informed, demanding customers to ensure timely and responsive resupply across the battlefield.

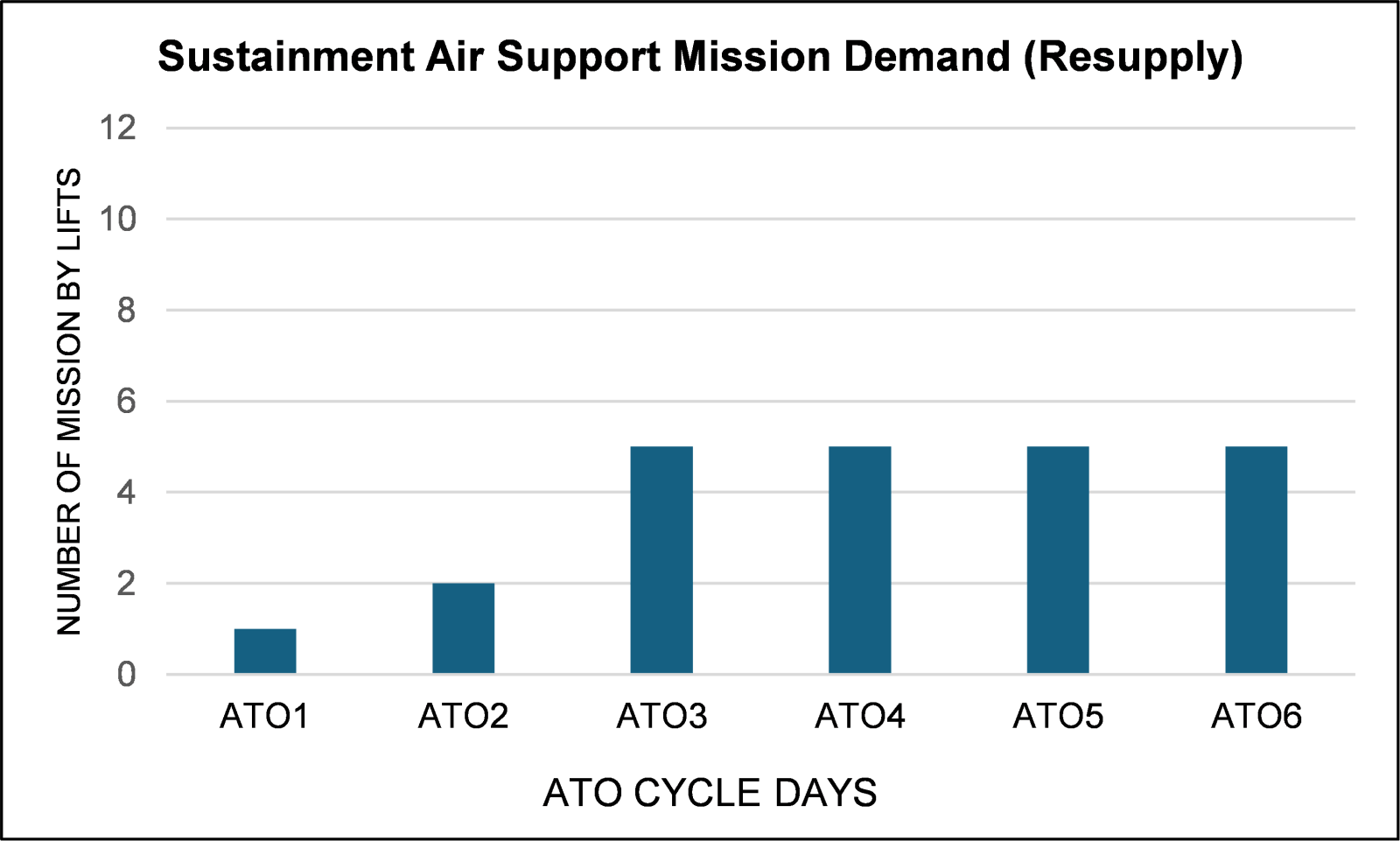

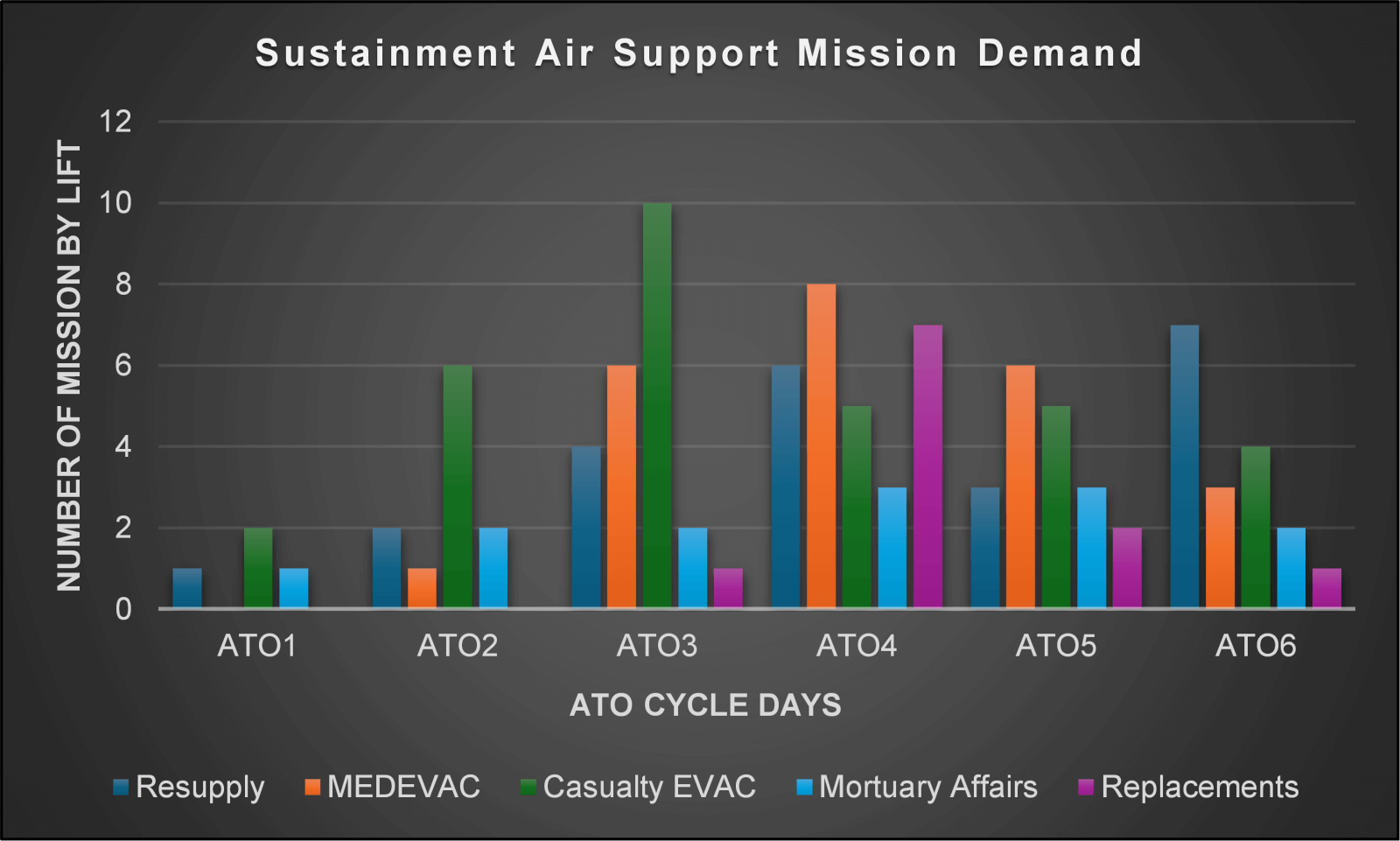

The possession of air assets is only part of the equation when understanding the potential value of using aerial resupply; effectively utilizing those assets is equally crucial. Based on my recent experience in two distinct exercises, I observed that sustainment rotary wing air support was initially underutilized. In both cases, the 593rd Corps Sustainment Command (CSC) was assigned direct support of several rotary wing assets, only to discover that these assets were not being fully utilized at the outset. After assessing the situation, we determined that the optimal approach was to employ a combination of ground and air assets in parallel, tailoring their use to the specific mission requirements and the environmental conditions best suited for air or ground operations. I gained a better understanding of the real problem during a deep dive into aerial resupply that occurred in an Assessments Working Group (AWG) at the recent Freedom Shield 2025 exercise. When we initially started the AWG, rotary wing assets were not fully integrated into the sustainment plan, leading to delays and inefficiencies in critical logistics operations. As the battle evolved, the demand for air support surged, particularly in areas with difficult terrain that hindered ground transportation. The growing dependence on rotary assets for time-sensitive operations, such as medical evacuations (MEDEVAC), casualty evacuations (CASEVAC), and resupply missions, has become increasingly evident. This trend highlights the value of rotary assets in enhancing operational flexibility and speed. In response, we developed a concept to categorize each air support mission based on demand, dividing them into key categories: Resupply, MEDEVAC, Casualty EVAC, Mortuary Affairs, and Personnel Replacements. This air support mission demand analysis was grounded in forecasted sustainment requirements for the upcoming Air Tasking Order (ATO) cycle days.

After the first session of the AWG, it quickly became apparent that our initial approach had been based on an incorrect understanding of distribution and fast resupply needs. Figure 1 clearly illustrates this shift in thinking, revealing that our initial focus was solely on resupply without considering the broader scope of sustainment distribution. As a result, we overlooked critical variables, including medical support and human resources. Upon reassessment, we refocused on the actual distribution requirements of the Corps, extending our analysis beyond simple commodity resupply. This broader perspective allowed us to expand our understanding of sustainment demands, significantly increasing the need for air support, as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Through this revised approach, it became clear that the primary drivers of air support demand were medical operations—specifically CASEVAC and MEDEVAC—and human resource support, such as personnel replacements.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 2

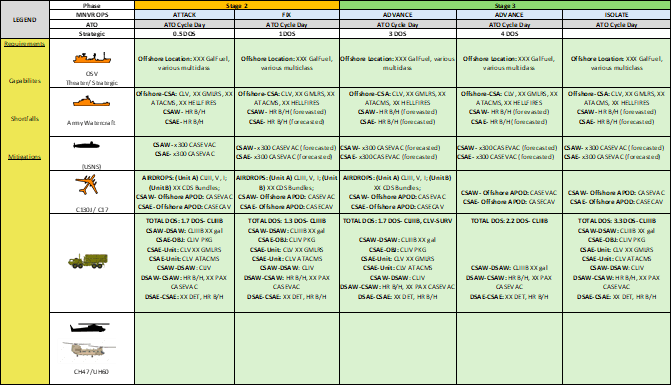

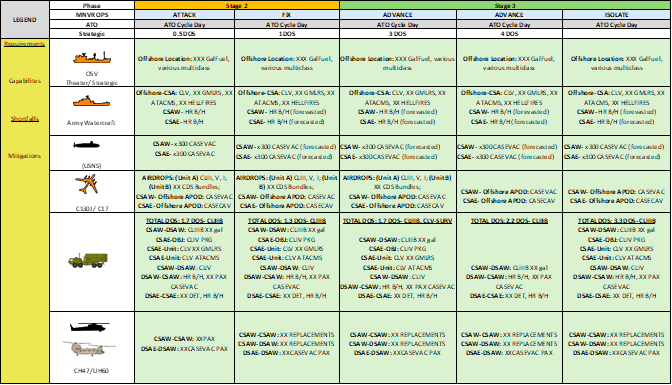

To further illustrate the disparities in the employment of rotary-wing air support and emphasize the need to diversify our transportation methods, we analyzed the Tactical Movement Table (Figure 3) from our recent Warfighter exercise. This visual representation, which captures movements by land, sea, and air, highlights the initial underutilization of rotary-wing assets during the first phase of the operation. However, during the second phase, after deliberately integrating all available modes of transportation—with particular emphasis on rotary-wing support for CASEVAC, MEDEVAC, and human resources movement—we observed a marked improvement in resupply speed and operational distribution. This shift is reflected in Figure 4, which demonstrates a more balanced and optimized use of rotary-wing assets.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4

Applying Air Support Integration to DOTMLPF Framework

To achieve lasting change in how the U.S. Army integrates air support into sustainment operations, it is essential to approach the issue through the DOTMLPF framework—Doctrine, Organization, Training, Materiel, Leadership, Personnel, and Facilities. This structured approach ensures that improvements are not isolated fixes but are institutionalized across the force, enabling readiness and adaptability in complex, contested environments like the INDOPACIFIC region. The integration of aviation into sustainment is often treated as a peripheral concern, with helicopters seen primarily as maneuver assets or emergency options. To fully harness the potential of air-enabled logistics, the Army must transform its policies, force structure, training methodologies, and leadership mindset.

Doctrine is the foundation upon which operational behavior is shaped, and current doctrine underrepresents the critical role of aviation in sustainment. Key doctrinal manuals such as FM 4-0 [3](Sustainment), ATP 3-35 (Army Deployment and Redeployment), [4] and ATP 4-16 (Movement Control) [5]should be revised to clearly articulate when and how aviation assets—particularly rotary-wing platforms like the CH-47 and UH-60—can be employed for logistical purposes. These revisions should embed air resupply as a core sustainment function rather than a contingency or last resort. In particular, doctrinal updates must offer explicit guidance on integrating aerial movement into the LOGSYNC matrix, the synchronization tool used to align logistics efforts across warfighting functions. Doing so will elevate the perception of air sustainment as an integral, planned, and prioritized component of logistics operations.

From an organizational standpoint, existing sustainment formations lack the permanent structures and relationships necessary to enable effective air logistics. Corps Sustainment Commands (CSCs) and Sustainment Brigades must establish embedded aviation coordination elements (ACEs). These elements should consist of aviation planners, G3 Air liaisons, and sustainment officers with aviation and joint logistics experience. Permanently assigned to these units, ACEs would facilitate proactive planning and real-time execution of aerial resupply missions. Additionally, habitual coordination relationships should be formalized between sustainment units and Combat Aviation Brigades (CABs), mirroring the integration seen between maneuver and aviation elements. Creating standing liaison teams that train, deploy, and operate together will foster trust and operational fluency. As operations shift toward more distributed models—whether in archipelagic environments or remote mountainous terrain—units must be organized into smaller, modular logistics nodes capable of operating independently and receiving resupply through the air.

Training must evolve to support this new operational reality. Combat Training Centers (CTCs) and Warfighter Exercises (WFXs) must incorporate realistic air logistics scenarios that require sustainment and aviation units to plan and execute together. For example, simulated enemy interdiction of ground lines of communication should drive sustainers to request CH-47 lift missions for critical parts, forcing coordination across staff functions and echelons. Sustainment planners must also become proficient in contributing to and interpreting the Air Tasking Order (ATO), which governs how aviation missions are scheduled and approved. Understanding the ATO allows logistics planners to advocate for sustainment missions and deconflict them with other aviation tasks like air assault or medevac. These skills must be built through repeated, hands-on experience, including air movement drills, sling load planning, and aerial delivery coordination. Battalion and brigade sustainment units should integrate these rehearsals into home-station training to build muscle memory and readiness.

Addressing the materiel domain, the Army must recognize that current rotary-wing platforms, while effective, have limitations in capacity, range, and survivability—especially in contested airspace. Investment should focus on emerging technologies that enhance distributed logistics capabilities. Cargo-capable unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) represent a promising solution for resupply missions in high-risk or denied environments, capable of transporting 300–500 pounds of materiel autonomously. Precision Airdrop Systems (JPADS) offer another solution, enabling high-altitude deliveries with GPS-guided accuracy, minimizing exposure to threats while sustaining dispersed forces. Additionally, rapid load/unload systems and optimized rigging equipment can significantly improve aerial logistics turnaround times and reduce mission footprint. This precision minimizes risk to aircraft and personnel, enables resupply in other inaccessible locations, and aligns with emerging doctrinal imperatives that emphasize flexibility, survivability, and contested logistics. The system supports the Army’s shift toward multi-domain operations and directly enhances the agility of sustainment formations operating forward of brigade support areas.

Leadership is pivotal in transforming organizational culture and ensuring that new capabilities are adopted and sustained. Leaders at all levels, particularly within sustainment formations, must shift their mindset to view aviation as a logistics enabler rather than solely a maneuver asset. This cultural change must be reinforced through Professional Military Education (PME). Courses such as CAS3, ILE, and SAMS should integrate modules on aerial logistics, air mission planning, and aviation asset capabilities and constraints. Leaders educated in these topics will be better positioned to advocate for and employ air logistics in both planning and execution phases. Moreover, leadership emphasis on aerial sustainment will cascade down to subordinate units, encouraging innovation and initiative in the use of aviation for logistics.

In the personnel domain, the Army must ensure that the right expertise is present in the right places. Aerial logistics coordination roles—such as aviation planners, G3 Air liaison officers, and air movement officers—must be fully staffed and integrated into sustainment planning cells at the division and corps levels. These roles should not be collateral duties or temporary assignments; rather, they must be institutionalized as core positions with clear career pathways and required training. Cross-training initiatives can further expand this capability, enabling sustainment officers and NCOs to attend aviation-related courses such as the Sling Load Inspector Course, Aerial Delivery, or FARP Operations training. Building a bench of sustainers with aviation fluency will enhance planning and execution across the force.

Finally, facilities must support expeditionary and distributed aerial logistics. Forward logistics elements require infrastructure similar to Forward Arming and Refueling Points (FARPs), adapted for sustainment purposes. These mobile platforms must be capable of supporting rotary-wing operations with fuel, sling load staging, basic repair services, and temporary storage. The ability to quickly establish and displace such nodes will be critical in future conflict environments characterized by mobility, dispersion, and anti-access threats. Sustainment units must also possess the engineering capacity and authority to construct temporary helipads, drop zones, and landing sites to enable aerial resupply across the battlespace.

Final Thoughts and Considerations

In conclusion, several considerations can be made to enhance the efficiency with which we utilize, incorporate, and integrate air support into military formations, particularly for faster resupply. One key approach could involve the coordination of subject matter experts, such as Combat Aviation Brigade (CAB) leaders, within the Corps Sustainment Command (CSC) to oversee air support operations. In the short term, a practical solution might be to ensure that when aircraft like CH-47s and UH-60s are assigned to missions, aviation personnel are also designated to facilitate communication and coordination for air operations. Maximizing the use of the DIV and CORPS G3 Air shops, CAB LNOs to DMAIN and DREAR and BCT Aviation officers will drive the utilization. This ensures consistency at the tactical level by having an individual on the ground who is well-versed in aviation terminology, streamlining the coordination process. The additional efforts, time, and personnel invested in planning aviation sustainment concepts of operations yield tangible benefits, as demonstrated during WFX and FS. In the long term, we learned it may be beneficial to implement a structural change within task organization, permanently embedding aviation assets within the CSC framework, along with the necessary personnel for comprehensive management and coordination of air support operations. This approach would improve the overall effectiveness and responsiveness of air support in military operations. Furthermore, to ensure widespread and sustained effectiveness, these coordination practices should be incorporated into sustainment doctrine and validated at CTC rotations and WFX; not just as ad hoc initiatives but as deliberate injects to assess operational readiness in complex theaters. Additionally, the integration of aviation into Army sustainment must be addressed comprehensively through the DOTMLPF framework. By revising doctrine, embedding aviation planning capabilities into sustainment organizations, enhancing training realism and frequency, investing in next-generation logistics platforms, educating leaders, staffing specialized coordination roles, and constructing appropriate facilities, the Army can transform air logistics from an improvised capability to a deliberate and reliable operational advantage. This shift will not only improve agility and responsiveness but also ensure sustainment operations can succeed across the full spectrum of future conflict—from peer adversaries to humanitarian missions. For junior soldiers preparing sling loads to general officers orchestrating theater-level operations, this transformation is essential to preserving combat effectiveness and operational reach. In alignment with the closing remarks of General Randall Reed, Commanding General of United States Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), at the Spring 2025 Joint Deployment and Distribution Enterprise Board (JDDEB), who stated, “We have to stop learning the same lessons from our real-world operations and exercises and implement a permanent solution,” I believe these final considerations represent a meaningful step toward achieving that goal—particularly in the context of improving air rotary-wing support for sustainment operations.[6]

1 Eric Landry, “Fortifying Operational Readiness in the Pacific,” Military Review, January–February 2024, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/English-Edition-Archives/January-February-2024/Landry-Pacific/.

3 Field Manual (FM) 4-0, Sustainment (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, July 2023).

4 Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 3-35, Army Deployment and Redeployment (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, November 2022).