Understanding the Shift in Responsibility of Fires at Echelon

Understanding the Shift in Responsibility of Fires at Echelon

Synchronizing how Divisions and Brigades Fight with Fires to Achieve a Common Tactical Objective

“The thanks of the infantry, in my opinion, must be treasured more by every artilleryman than all decorations and citations.”

-Georg Bruchmüller

3rd Battalion, 6th Field Artillery Regiment

1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team

10th Mountain Division (LI)

Prepared by: LTC Andrew Zikowitz, CPT James Sloss, CW3 James Crain

Foreword

This paper is designed to orient military professionals from the United States Army on achieving success in Large Scale Combat Operations through the understanding and application of how the Fires Enterprise fights at echelon, namely the Army Division and the Army Brigade Combat Team. The following analysis of Fires at the Division and the Brigade is based on doctrine and requires a firm understanding of both the art and science of the Fires Warfighting Function.

Implementation of the Fires Warfighting Function at echelon foundationally does not change by new emerging technologies. However, with Force Design Updates, utilization of traditional or organic fires assets that were once present within a Brigade Combat Team changes the operational framework, targeting horizons, and realistic expectation of effects of downtrace organizations.

ARSTRUC 2025-2029 is reframing the way we fight, placing the division as the unit of action and moving enabling capabilities previously found in Brigade Combat Teams to the division level. Those assets are the brigade intelligence support element and the brigades organic unmanned ariel systems. Additionally, the cavalry squadron has been removed entirely from light infantry division. Soon, Division Artillery will retain the Field Artillery Battalions, and the Brigade Engineer Battalions will be dismantled and converted into Engineer Brigades. FM 3-0 states historic BCTs can only focus on operations within 12 to 24 hours and have an operational reach of 5 to 25 KMs. As a result, the maneuver brigade must change how they fight. The brigade will rely on the Division for enabler support to set conditions in the close through task organization, sustainment, and fires.

Andrew F. Zikowitz

Lieutenant Colonel, U.S. Army

Commanding

Introduction

The Army’s tactical unit of action for the last two decades has been the Brigade Combat Team. Through force design analysis, the Army designated the division as the principal warfighting formation and initiated Army Structure 2025-2029 (ARSTRUC 25-29), effectively transitioning Brigade Combat Teams (BCT) back into brigades. The force design presents a new problem set for maneuver brigades with integrating fires into their maneuver plan. BCTs became accustomed to looking deep within their Area of Operation (AO) to conduct targeting and shaping operations for subordinate maneuver battalions. Brigades are not self-contained, independent formations post-ARSTRUC as they lack the necessary capabilities to target in the deep area or shape operations any farther than five kilometers from the forward line of troops (FLOT) with organic mortar systems, as a result they will rely heavily on support from their higher headquarters to task organize for combat.

ARSTRUC directly impacts how a maneuver brigade and its higher headquarters fight with fires. Brigades cannot fight with fires as they have in the past because the field artillery battalion is realigning with the Division Artillery (DIVARTY), the Cavalry Squadron is removed, the Brigade Support Battalion moves to the Division Sustainment Brigade, and the Brigade Intelligence Support Element (BISE) is reassigned to the Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Battalion. Additionally, Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), at the company and brigade level, are in the divestment process and are no longer in use. The loss of these capabilities altered the brigade’s ability to find and fix deep enough to conduct targeting. The initiation of ARSTRUC without updated doctrine to direct formations how to fight created a gap in understanding in regard to fires. As a result, it is essential to analyze the roles and responsibilities of fires at echelon, reevaluate key development positions of field artillery officers to maintain current Fire Support Coordinators (FSCOORD) proficiencies, review how the force trains to fight in a contested operational environment against a near peer threat to fight and win tomorrow’s war, and continuously update doctrine.

A Division’s Battlefield Defined

Division commanders focus on conducting decisive, shaping, and sustaining operations simultaneously throughout their AO, while BCTs focus on the close fight. Within the assigned AO, the means and model to organize the Division’s conceptual framework is through the identification of the deep, close, and rear areas. This model is more commonly used and remains useful in understanding the timing, spacing, and focus of planned operations. Today we must assess whether this framework remains relevant post-ARSTRUC.

Deep Area: The deep area is where the Commander sets conditions for future success in close combat.

Close Area: The close area is the portion of the Commander’s area of operations where many subordinate maneuver forces conduct close combat.

Rear Area: The rear area is an area where most of the forces and assets locate that support and sustain forces in the close area.

The Division spends the preponderance of its time addressing problems within the geographical space labeled “Division deep area.” This is the space in which the enemy’s long-range fires and air defenses reside. To create favorable ratios and achieve attrition, present multiple dilemmas, and properly set conditions for subordinates’ success, the Division must focus on the integration and synchronization of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets paired with multidomain delivery capabilities. The Division targeting enterprise must constantly focus on the deep to set conditions in the close, while forecasting support nested with the Air Tasking Order (ATO) cycle for future allocation. If the Division targeting collective finds itself focusing on close operations, the potential of failure increases exponentially.

Close Area Operations involve tactical actions and is where maneuver and fires unite to close with and destroy the enemy. Regarding the Division, the maneuver brigade makes up most forces for the close fight. Operations in the close area are inherently lethal because they often involve direct fire engagements with enemies seeking to mass direct and indirect fires on friendly forces.

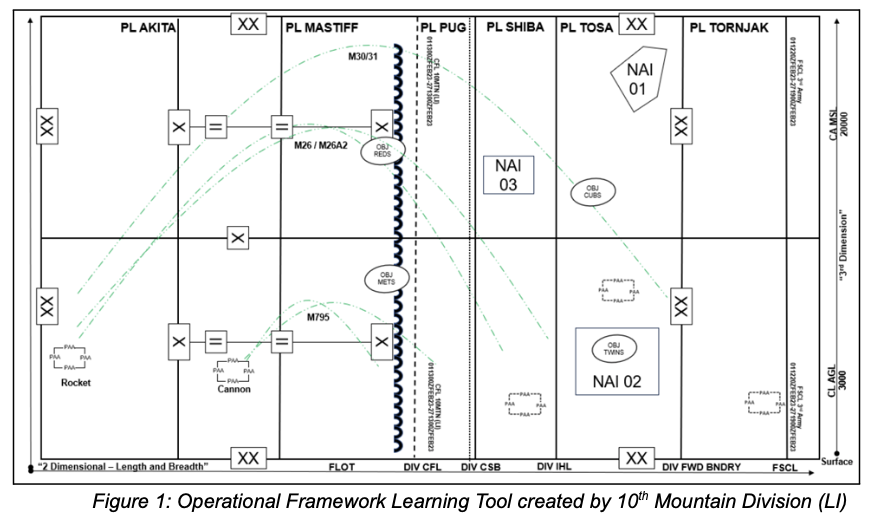

Figure 1 is a teaching tool created at 10th Mountain Division (LI) to educate Brigade and Division Level staff on the importance of numerous components within the operational framework. The operational framework contains more than establishing rear, close, and deep areas. It also includes identifying boundaries, clear and identifiable Fire Support Coordination Measures (FSCMs), common sensor boundary for the use of target acquisition systems, and an Intelligence Handover Line to delineate the responsibilities of collection assets between the Division and BCT, among others. By properly building the operational framework, the deep, close, and rear areas remain relevant post-ARSTRUC. Echelons must then define the fight they are responsible for.

A Division’s Fight

Divisions must be able to provide intelligence, deep fires, and logistics to ensure the survivability and dominance of brigade combat teams on future battlefields.

–GEN Rainey and GEN Potter

The primary purpose of a division remains to win battles and engagements during Large Scale Combat Operations (LSCO). To do so, division commanders seek to create multiple dilemmas for the enemy, while simultaneously creating opportunities for friendly forces. Divisions create opportunities by balancing risk in areas to mass the effects of combat power at the decisive point. The division’s responsibility is to synchronize the effects of all domains, to set conditions on the battlefield, and to task organize subordinate units to accomplish its mission.

Divisions set conditions for subordinate brigades by identifying the enemy’s course of action and attrition of the enemy force into a manageable element their subordinate brigades can defeat in close combat. They employ capabilities to disintegrate the cohesion of enemy follow-on forces, reserves, and short- and mid-range fires which threaten close and rear operations to provide time and protection for subordinates. Divisions enable the success of operations by synchronizing indirect fire, electronic warfare, attack aviation, and close air support. If the Division fails to shape the deep area and set proper conditions, the brigade may face an opposition with unfavorable ratios resulting in early culmination, disrupted tempo, and loss of momentum. The division task organizes to enable success, but task organization changes are made in discrete windows with specific parameters. The commander continuously allocates and re-allocates combat power under division control to support its brigades to ensure the ratio remains favorable. The most common manner a division task organizes is allocating rotary-wing or additional artillery assets to support a maneuver force. Of note, a division that continuously allocates assets to support the close area due to conditions not set for subordinates creates a cascading effect into the targeting cycle, which can quickly result in constantly shortchanging deep condition setting. This creates a negative cycle of allocating assets and never setting conditions. Divisions focus must remain setting conditions in the deep area.

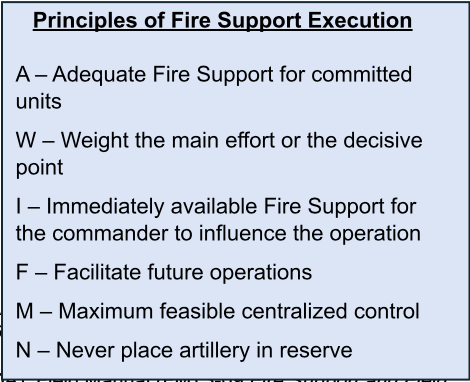

When Divisions task organize artillery battalions, commanders and staff must utilize the principles of Fire Support execution, commonly referred to as “AWIFM-N”. The principles of Fire Support execution guide commanders and staff’s decision by highlighting the fundamental rules of artillery. The most notable principle being to weight the main effort or the decisive point. This principle stresses the rule to support the operation, which directly accomplishes the mission. The rule also implies a maneuver brigade who is not the main effort might not receive artillery. At times, brigades will have to close the distance between their subordinate battalions and the enemy exclusively with their organic mortar systems.

Maneuver brigades must understand Divisions fight to attrit enemy forces in the deep area. The Division’s attrition operations set conditions for the brigade to successfully complete their mission. If the Division fails to set favorable conditions, the Division Commander must make a decision to either task organize the brigade or slow the tempo of the operation to allow time to set the proper conditions.

Brigade Fight with Fires

The brigade’s focus in LSCO is to close with and destroy the enemy with direct fires enabling it to seize, control, clear, or hold terrain. Divisions must be enemy focused and must shape the fight in favor of the brigade. This allows brigades to use fires to suppress and neutralize enemy forces enabling their formations to close with and destroy the enemy. Brigades no longer target specific enemy assets in a deep area due to the inability to conduct

doctrinal targeting.

Targeting is a complex and multi-disciplined effort which requires coordinated action among all warfighting functions. Targeting requires the ability to utilize the Army Targeting Methodology, which consists of the ability to decide, detect, deliver, and assess (D3A). For the past two decades, the Infantry Brigade Combat Team had the tools needed to conduct the D3A methodology, but due to force design updates resulting in the loss of the cavalry squadron and organic small UAS, brigades of the future do not possess or control the means to “detect” in the deep area without the re-tasking a maneuver force. As a result, the targeting process used in the future will mirror methods used during AirLand Battle and FM 6-20-10 (The Targeting Process) which integrates “targeting” into the brigade’s operations process. Brigades will utilize their higher headquarters targeting meetings to feed information up and request needs required to complete the assigned mission.

|

Lessons Learned During JRTC 24-07 During Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC) rotation 24-07, 1BCT, 10th MTN DIV (LI) (Warriors) retained the BISE and organic field artillery battalion but lost Shadows and Ravens through the divestiture process, the cavalry squadron, and anti-tank companies due to ARSTRUC. 1BCT was augmented with two British Reconnaissance Companies (COYs) from the division reconnaissance. The Warrior Brigade used the British COYs as a dismounted reconnaissance element to support the Brigade’s information collection requirements. Additionally, the fire support teams, which were previously supporting the cavalry squadron supported the British COYs in integrating fire support into their reconnaissance effort. 1BCT conducted a Joint Forcible Entry (JFE) by way of air assault, simultaneous amphibious assault, and air-land operation. The brigade understood this was a 10th MTN DIV operation where 1BCT was the main effort and would remain heavily supported until the air-land operation was complete. Upon completion, the 10th MTN Division transferred authority to the 21st ABN Division, and 1BCT shifted to third out of three elements in priority of fires. 1BCT struggled to establish accurate understanding of the enemy. The Brigade overestimated the capacity of the UK Coys and attempted to fill the reconnaissance gap by pushing maneuver forces forward to confirm or deny suspected enemy activity and to create a proper security zone. These efforts failed and created a lack of understanding that degraded and desynchronized the targeting process. Additionally, the BCT Target Working Groups were effectively rehearsals for the Target Coordination Boards; they lacked proper inputs and did not provide a clear understanding of the operation or generate decision points for the commander. 1BCT anticipated deeper engagement areas for the defense; however, this did not come to fruition. Fortunately, with coaching by the OC/Ts and through the rapid decision-making process (RDSP), the plans cell successfully integrated the targeting process into the planning process. Once 1BCT integrated targeting with the planning process, they began to understand the enemy and properly identify the disruption, battle, and security zones and target entities within the serviceable areas. Previously, the BCT was concerned with enemy forces in the deep area which the unit could not organically identify or service, 1BCT utilized the now synchronized targeting and planning cycles to actively engage and create effects on the enemy in the close area. |

In the Army 2030 construct, brigades will use fires to close the distance between subordinates and the enemy. They must trust Division and Corps have prepared the battlefield and set conditions for them to succeed. Maneuver brigades must understand the deep area is not their fight and to focus on the close fight which entails closing with the enemy and destroying them to control key terrain.

Analysis and Recommendations

The way forward for the Fires Enterprise may seem straightforward. The artillery battalions will realign with DIVARTY, and the targeting methodology will remain unchanged as it has for the past 30 years. Yet there are areas which still need attention to aid the transition to the Division being the unit of action. Utilizing elements from DOTMLPF-P as a lens to focus discussions on specific areas. The following discussion addresses areas demanding attention as the Army transition to Large Scale Combat Operations.

Doctrine

The Fires Enterprise must assist shaping doctrine as the Army continues to update its library to codify the shift from Unified Land Operations to Multidomain Operations. Updates to doctrine must stress that maneuver brigades do not have a deep area, and they must plan fires to suppress and neutralize enemies to support their subordinate units. Targeting is not a feasible goal for brigades during LSCO due to the range capability of the M121, 120mm mortar system, as their primary organic indirect fire system unless the division task organizes a field artillery battalion to support the brigade combat team.

Large-scale conflict is nothing new to the United States military. The technology has changed, but the tactics and techniques remain the same. FM 100-5 (Operations), which introduced AirLand Battle, FM 6-20-10 (The Targeting Process), FM 6-20 (Fire Support in the AirLand Battle) are publications used during the pre-counter insurgency era. Each of these doctrines are references of how divisions fight during LSCO. Although the Army’s focus is on LSCO, we must maintain balance in doctrine to cover both linear and non-contiguous conflicts.

Leader Development

The Field Artillery branch is unique in comparison to other Army branches due to how early officers develop skills to widen their view and influence outside of their organization. Lieutenants and captains develop and refine the skills of working with and alongside other service members from different branches, while majors hone their acquired skill base. As the direct support artillery battalions realign under DIVARTY, the glide path of professional development for field artillery officers becomes uncertain, namely centered around developing field artillery officers to serve as a FSCOORD. The uncertainties are based on the shift of responsibilities at echelon and the alignment of field artillery units to maneuver brigades.

Foremost, we must account for how we develop leaders to manage working for two commanders. Artillery officer development is unique and by the time they are Battalion Fire Support Officer (FSO) they must master working for a Maneuver Commander and an Artillery Commander. During this time, junior captains develop the skills to process information and communicate it to their Commanders. If this skill is not mastered as a captain, success as a major is more difficult as they also transition from direct to organizational leaders. An artillery officer will serve two commanders again as the BDE FSO. At this level, majors are no longer learning and developing skills but are practicing the skills. The BDE FSO position requires an array of skills necessary for success while serving as a FSCOORD. These skills include multitasking, vertical and lateral communication, and organizational perspective.

With artillery leaving the BCT and echelons above brigade responsible for setting conditions for subordinates with artillery, attack aviation, and close air support, there is reduction in the responsibilities of the BDE Fire Support Officer. Currently, Department of the Army Pamphlet (DA PAM) 600-3 recommends commanders fill the BDE FSO position with the unit’s “best and senior” major, but we risk the position transitioning to resemble the Combat Aviation Brigade FSO position where the FSO ends up being an additional senior planner for the BDE. With minimal assets to leverage, this position no longer develops the knowledge or skills in Combined Arms Operations as it does currently. A position to better suit the development of Battalion “best” major is the Division FSO. The position will give majors insight of how division manages fires and allocates to subordinates, while stressing other key skills essential to serve as a FSCOORD.

Leaders at echelon must ensure artillery officers are continuing to develop their skills to be successful. As the artillery battalions leave the BCT, there must be a deliberate plan to align Battalion FSOs to a unit. This is a crucial position to develop young artillery officers. Additionally, the Army must reevaluate key development positions for majors. The Brigade FSO position will not need the Battalion’s most senior major in LSCO.

Training

As the Army changes the way we fight, we must adapt and change the way we train. Commanders and leaders at echelon are responsible and accountable for the training of their unit. These leaders must first understand how we fight, so they can create tough, realistic training, which replicates the problem sets faced on the future battlefield.

The following areas require consideration while planning training:

- Division Collective Training: It has been over twenty years since the Army fought with a division in large-scale combat. The last time a division was the unit of action was 2003 during the Iraq Invasion. During the intervening years, Division Headquarters across the force have participated in multiple Warfighter Exercises to maintain their proficiency. These exercises simulate combat scenarios to stress the division staff’s duties and responsibilities, and the headquarters systems and processes. The disadvantage to a Warfighter Exercise is it is behind a computer screen, without Soldiers or formations providing bottom-up refinement, executing the plan, or introducing the fog of war.

Starting in 2020, the Army began to send Division Headquarters to National Training Center (NTC) to train with their subordinate. Leaders have dubbed this effort “divisions in the dirt.” This initiative gives the Division Headquarters a real repetition of maneuvering their subordinate brigades, setting conditions in their deep area, and fighting a free-thinking enemy force.

Currently, “divisions in the dirt” target audience is Armor Divisions due to the nature and size of NTC. The Army needs to expand on this training event and find a location which suits a light infantry division. Warfighters are important training events, but it does not hold the same value as moving actual forces across a battlefield.

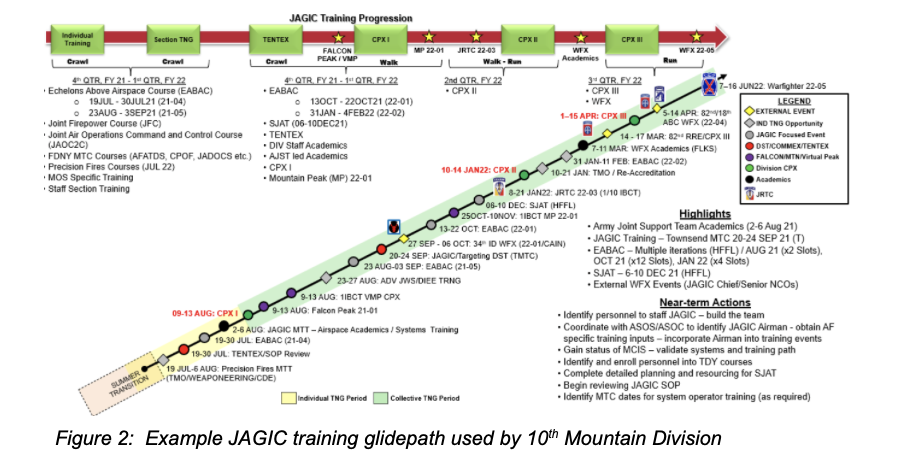

- Joint Air-Ground Integration Center (JAGIC): The JAGIC is the execution arm of the Division’s targeting effort; however, to safely employ surface-based fires, joint force air component, and Army aviation assets, the JAGIC must posture itself to control airspace. To achieve success, the JAGIC must have focus and the correct personnel with the right training and systems proficiency to implement the Unit Airspace Plan and execute the Airspace Control Order and Air Tasking Order. As the recipient of the daily targeting plan, the Division JAGIC requires training maintenance. Twenty-four positions (if fully manned) across multiple sections and organizations make this an incredibly hard task. To mitigate catastrophic failure in the airspace and target execution phase, the Division must leverage opportunities to enhance its ability to work together and meet routinely.

- Forward Observers: The Field Artillery needs to get the forward back in forward observers (FO). At the company level, we must train and empower our Company Fire Support Teams (FiST) to operate autonomously forward of the FLOT. Brigades no longer have a calvary squadron forward to identify the disposition and composition of our adversaries. The Fires Enterprise must rebuild the trust and confidence with our maneuver counterparts. Once we establish trust, we can employ our FiST in different options rather than FOs staying with the infantry Platoon Leader and decentralized from the FiST. The employment option to pursue is Company or Battalion Fire Support Teams which centralizes the FiST at the Company or Battalion level. These options allow FSOs at echelon to establish the Forward Observers in front of the FLOT in Observation Points. Well-trained and trusted observers can fill part of this gap of the Cavalry squadron’s removal. Additionally, just like every Soldier is an infantryman, every Soldier is a sensor. A Brigade’s Fires Enterprises duty is to train our infantry counterpart our skillset to mutual support each other on the battlefield. All artillery Soldiers and leaders are stewards of the Fires profession and must embrace the culture of life-learning, seeking to master the basics, and continuously chasing the mil and second. Maneuver commanders must understand the importance of forward positioning of FOs and own their utilization through “tasks to subordinates.”

Conclusion

Due to the Force Design Update for Army 2030, the Brigade Combat Team is transitioning back to its former configuration as a brigade with no organic capabilities to be self-contained. Divisions will task organize brigades with enablers and prioritize the main effort with assets to complete missions in Large Scale Combat Operations.

Until the brigades are organized with reconnaissance assets, they will struggle to manage a deep area as doctrine lays out today and will be unable to achieve effects through doctrinal targeting to shape for subordinate battalions. In the meantime, brigades and divisions must train and execute multi-echelon efforts to shape the battlefield in favor of maneuver formations using fires and recon assets at higher echelons.

Brigades and divisions still have much work to do to before the Army 2030 force structure is in full effect. It starts with reviewing present and historical doctrine to grasp the roles and responsibilities of corps, division, and brigade. During the transition leaders work to bridge the capability gap between the current Brigade structure and the future structure to inform doctrine revisions. Our efforts should focus on recommendations to shape future doctrine, to prioritize development of field artillery officers at all levels to advance the branch’s ability to synchronize and integrate in support maneuver at echelon, and leaders at echelon building realistic training which exercises their formation’s ability to adapt to the constantly changing battlefield of LSCO.

Bibliography

Headquarters, Department of the Army. Army Techniques Publication Observed Fires. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2017.

———. Army Techniques Publications 3-09.42 Fire Support for the Brigade Combat Team. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2016.

———. Field Manual 3-0 Operations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2023.

———. Field Manual 3-09 Fire Support and Field Artillery Operations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2020.

———. Field Manual 3-60 Army Targeting. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2023.

———. Field Manual 3-94 Armies, Corps, and Division Operations. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2021.

———. Field Manual 7-0 Training. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2021.

Rainey, James, and Potter, Laura. “Delivering the Army of 2030.” War on the Rocks. Last modified August 6, 2023. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://warontherocks.com/2023/08/delivering-the-army-of-2030/.

South, Todd. “Divisions in the Dirt: The Army’s Plan for the Next Big War.” Army Times. Army Times, May 6, 2024. Last modified May 6, 2024. Accessed June 12, 2024. https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2024/05/06/divisions-in-the-dirt-the-armys-plan-for-the-next-big-war/.

Strong, Eric S. “Army Structure Memorandum Fiscal Years 2025-2029.” Official Memorandum. Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2024.