Deliberate versus Dynamic Targeting

By: BG(R) Mark Odom

How does a Division organize for targeting? Although Joint and Army doctrine presents dynamic targeting as a subset of the deliberate targeting process, multiple Warfighter exercises reveal Divisions uniformly cast aside their deliberate targeting plan on the day of execution and acquire and strike targets dynamically. Joint and Army doctrines do not clearly distinguish between deliberate and dynamic targeting. Why is the distinction between them important? First, a unit cannot improve a process it does not assess. Divisions do not track battle damage assessments for deliberate and dynamic targets separately and, therefore, do not know which process produced the result. Second, some commanders do not philosophically believe in the deliberate targeting process. From their perspective, the process is unachievable and inflexible. The outputs of the deliberate targeting process (e.g., target synchronization matrix) simply provide a methodology, not a deliberate plan, to take a deliberate approach to target dynamically. Third, access to space-based intelligence collection capabilities (e.g., GEOINT, SIGINT/ELINT, MASINT, and OPIR) and publically available information means Division collection plans no longer depend on fixed ground-based systems with limited operational reach to find targets (e.g. ground-based radars and reconnaissance). Instead, they use space and air-based platforms to acquire the majority of their targets, which can be employed dynamically and have few operational limits. Finally, if a commander believes the majority of his targeting will be done dynamically rather than deliberately, he would organize his intelligence enterprise differently. This is not to say a dynamic targeting process is better than a deliberate targeting one, but rather to contend that each approach has its pros and cons and demands a different organizational design to maximize its effect.

Does doctrine distinguish between deliberate and dynamic targeting? JP 3-30, Joint Air Operations, acknowledges “the deliberate and dynamic nature of the joint targeting process is adaptable through all phases of the air tasking cycle” but draws no clear distinction between them. JP 3-09, Joint Fire Support explains that “dynamic targeting produces targets of opportunity that include unplanned targets and unanticipated targets and those targets that meet the criteria to achieve objectives but were not selected for action during the current joint targeting cycle.” If a target was “selected for action” but found by a sensor and struck by an asset not allocated against it, does that constitute a deliberate target? One could seemingly adapt this definition to fit either the deliberate or dynamic targeting process.

ATP 3-60, Targeting, defines deliberate targets as targets “known to exist in the area of operations and have actions scheduled against them.” This definition ranges from specific “targets detected in sufficient time to be placed in the joint air tasking cycle” to general “targets on target lists in the applicable plan or order.” Nevertheless, this definition of deliberate targeting implies the identification of a specific target, location, and plan to strike and assess the target before the day of execution.

ATP 3-60.1 Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, And Procedures For Dynamic Targeting describes dynamic targeting as “integrated within the joint targeting cycle” and for “unscheduled” or “unanticipated” targets. This definition, like the one in JP 3-09, Joint Fire Support, fails to clarify what constitutes “unanticipated targets” (e.g., a target not on the high payoff target list [HPTL] or a target on the HPTL in an “unanticipated” location). It also offers no guidance for how commanders should reconcile collection requirements for assessing strikes on deliberate targets with the reallocation of collection assets to assess the results of strikes on dynamic targets.

The discussion of deliberate and dynamic targeting in ATP 2.01, Collection Management, could be interpreted as contradictory. On the one hand, it draws no distinction between deliberate and dynamic collection contending “preplanned collection enables the seamless transition from preplanned missions to dynamic tasking and cueing of assets.” Although it recognizes the dynamic component of deliberate targeting, ATP 2.01 claims “aerial dynamic retasking is any change to the ATO during execution” and “dynamic retaskings are those requests that divert existing missions to new priorities.” So, what is the limit on dynamism for a deliberate collection plan? ATP 2.01, however, goes on to clarify that “dynamic retasking requires a greater level of risk management, as the approved collection requirements are canceled to meet the retasking requirements” and “dynamic retaskings require a stricter approval process and an increased level of airspace coordination because airspace situational understanding by aircrews and air controllers is necessary.” The latter distinction appears only to address air-based platforms. What about the dynamic re-tasking of space and ground-based systems for GEOINT, SIGINT/ELINT, MASINT, and OPIR or more specifically, the analysis to support them?

Does the distinction between deliberate and dynamic targeting, therefore, require another set of lenses? For example, if a sensor has to be tipped and qued more than a kilometer or two from the planned/templated location of the target or to another named area of interest (NAI) several kilometers or tens of kilometers away from the sensor’s current location, does one still consider the target a product of the deliberate process? Can an NAI transition to a targeted area of interest (TAI) during the execution of the collection plan, and enable a strike and still constitute a deliberate target? If a unit has to clear air space or adjust the air space management plan during execution for either the employment of a collection or strike platform, does this qualify as part of the deliberate targeting process? Can a target “decay” in the deliberate targeting process? In short, the scenarios above run counter to the purported advantages of a deliberate targeting process and appear to be indicators of a dynamic one.

What approach can a Division take to targeting? Three exist: deliberate, dynamic, or a combination of the two. The deliberate targeting process is a deliberate plan to observe, strike, and assess a specific target at a specific location and time in the future. This approach has several advantages. First, deliberate planning and coordination reduce or eliminate coordination during execution. Second, a deliberate plan attempts to place the best sensor, strike platform, munition, or combination of sensors and strike platforms against a specific target and produce an air space management plan to enable their integration and angle of attack to achieve the optimal effect and assess the results of it. Third, deliberate targeting allows for the integration of non-lethal capabilities, which generally cannot support a dynamic targeting process. Finally, a deliberate approach often allows a unit to request and receive additional assets (collection and strike) and often outsource some of the analytical capability to support the plan. The biggest disadvantage of the deliberate targeting process is its rigidity. In short, it often cannot adapt to changes in friendly and enemy situations.

Conversely, the dynamic targeting process is focused on the current targeting cycle. A dynamic approach to targeting means the plan can be adjusted inside the ATO. And, if a deliberate approach is taken to dynamic targeting, the air space management, collection, and fire support plans and munition loads can be constructed to provide maximum flexibility. The dynamic targeting process has two principal advantages over the deliberate targeting process: flexibility and accuracy; it enables the re-tasking of collection assets and strike platforms based on actual enemy locations rather than templated locations.

The dynamic targeting process, however, has four disadvantages. First, the increased coordination and time to dynamically re-task assets often result in target decay. Second, the number of targets a Division can prosecute dynamically is finite, because dynamic targeting relies on the immediate processing and exploiting of intelligence to produce and decimate targets. It has a finite capacity or several self-limiting variables. Focusing the G-2 section’s analytical component to support dynamic targeting also detracts from the analysis of intelligence to support situational understanding to answer the commander’s priority intelligence requirements (PIR). Third, dynamic targeting often results in imperfect or suboptimal targeting solutions. Finally, dynamic targeting inhibits the integration of non-lethal capabilities into the targeting process.

Nevertheless, technological innovations have contributed to the proliferation of the dynamic targeting process at the Divison level. Collection plans no longer rely on a largely fixed architecture of ground radars, forward observers, and cavalry to acquire targets. A Division’s access to space-based intelligence collection platforms and, to a lesser extent, organic unmanned aerial vehicles, make switching focus from one NAI to another by tens or even hundreds of kilometers almost instantaneous and relatively easy, something unthinkable with ground-based radars and reconnaissance elements. The increased capabilities of both air and ground strike platforms also make their range a secondary consideration for targeteers. Technology, therefore, has made the Division’s targeting process inherently less dependent on the predictive analysis of an enemy’s future disposition and more reliant on a real-time capability to find, fix, and strike targets dynamically throughout the entirety of its area of operation.

Finally, a Division can also use a combination of dynamic and deliberate targeting processes, which allow it to focus on two different time horizons simultaneously. Most Divisions unconsciously choose this approach to targeting albeit without much thought to the organization and processes required by each one and their respective advantages and disadvantages. The questions, therefore, become does a Division plan to target primarily using the deliberate or dynamic process and how does it organize to maximize the effectiveness of its principal approach? While the principal advantage of the deliberate targeting process is capacity or the number of targets it can produce and prosecute, the advantage of dynamic targeting is accuracy or likelihood of hitting them. Nevertheless, the Division ought to organize its people and systems around the targeting process it plans to use in prosecuting the majority of its targets.

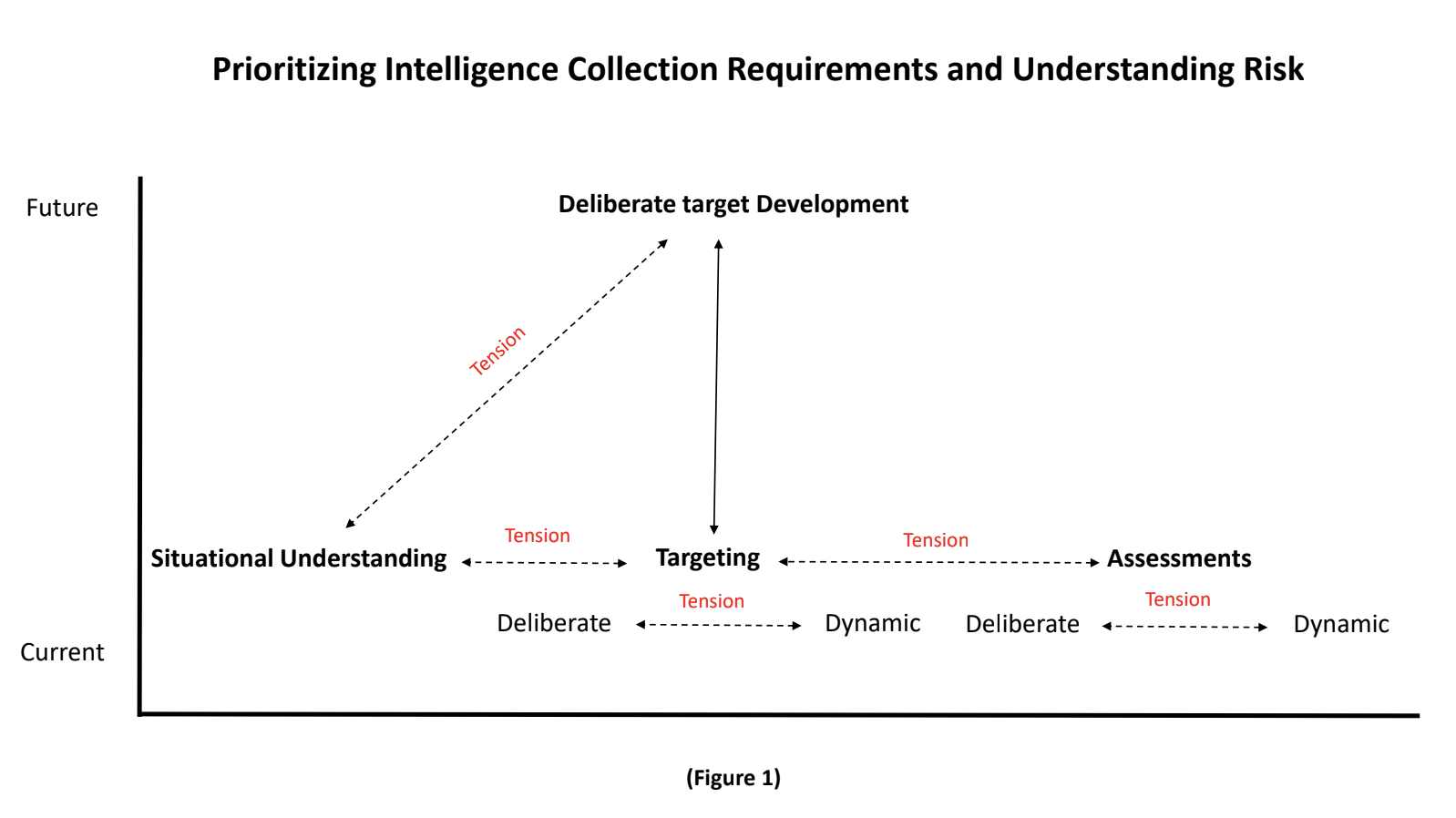

What are the doctrinal and organizational implications for the collection plan? Regardless of whether or not a Division takes a deliberate or dynamic approach to targeting, the commander still has to allocate his collection assets against three general and five specific requirements: situational understanding to satisfy his PIR; targeting (deliberate and dynamic) to address his high pay-off target list (HPTL); and assessments of targets (deliberate and dynamic) [see figure 1]. In some cases, the allocation of assets is immaterial because an asset used to answer a priority intelligence requirement cannot be used for targeting. But, if a commander does not understand the allocation of his collection assets against these five specific requirements, he cannot understand the risk he has assumed concerning the natural tensions that exist between his priorities for situational understanding, his PIR, and his priorities for targeting and assessments, his HPTL, and the more nuanced tensions between the simultaneous execution of both dynamic and deliberate targeting and dynamic and deliberate assessments. Commanders have a responsibility to reconcile the competing priorities in the collection plan, particularly those between the PIR and HPTL, and not leave it to their G-2 to sort out.

Prioritization of collection also implicitly requires the prioritization of analysis. How do G-2s internally reconcile the priorities of analysis between answering PIR and the targeting priorities established by the HPTL? In practical terms, dynamic targeting requires more analytical effort than deliberate targeting because the former is more constrained by time. So, do the priorities for analysis mirror the priorities for collection, or do they differ and how does a unit organize to account for these differences?

What implications do the deliberate and dynamic targeting processes have on the development of the collection plan – the size of NAIs, integration of collection assets, and scheme of maneuver? The deliberate targeting process requires refined NAIs defined in terms of one to two square kilometers or less. During Warfighter exercises, however, Division NAIs are tens of square kilometers by hundreds of square meters and remain unchanged throughout the 96-hour targeting cycle, in other words, it becomes difficult to imagine how they will transition to TAIs and targets to support a deliberate targeting process. At some point, NAIs should become refined to a point that requires minimal tipping and cueing of assets during execution. The scheme of maneuver for a collection plan that supports a deliberate targeting process is pre-determined and in line with the high payoff target list and should require only a modicum of coordination and command and control or “on the loop” command and control. The collection and fusion team in the Analysis Control Element (ACE) arguably possesses the ability to oversee this level of effort where adjustments to the plan are the exception, not the norm.

Conversely, a dynamic approach to targeting does not require the same level of precision. A collection manager might deliberately construct large NAIs to group targets and/or target sets to enable dynamic tipping and queuing the re-tasking of intelligence assets. In the dynamic targeting process, the scheme of maneuver for a collection plan might prioritize collection by NAI or groups of templated targets rather than based solely on the HPTL or individual targets. A collection plan for dynamic targeting has many more variables at play (type of target, location of next target, flight times for aerial sensors, station times for collection and strike assets, inbound collection and strike assets, the importance of BDA, etc.) and, therefore, choices with respect, not only to fixing, striking, and assessing a target but for transitioning both collection and strike assets and analytical capabilities from one target to another. The requirement to command and control a collection plan for dynamic targeting, therefore, is no longer an “on the loop” function a commander can relegate to specialists and warrant officers in the ACE, but an operational one that cannot be disaggregated from the Joint Air Integration Center (JAGIC) and Current Operations Information Center (COIC).

So, what are the organizational implications for the dynamic targeting process? First, targeting dynamically requires the integration to some degree of GEOINT, SIGINT/ELINT, MASINT, and/or FMV. This means dynamic target development is limited to the number of GEOINT, SIGINT/ELINT, and FMV teams or groups of analysts and systems a Division can produce. In most cases, a Division can assemble a single team to provide 24-hour coverage without augmentation from an Intelligence Electronic Warfare Battalion or Expeditionary Intelligence Battalion. In short, if a Division takes a dynamic approach to targeting, it needs to think about how it creates two or three, or four teams.

The Field Artillery Intelligence Officer (FAIO) is another limiting factor in the dynamic targeting process. He can only physically shack up a finite number of targets per hour. One option is to increase the number of FAIOs. Another way to increase target output is to make the Division’s most capable targeting warrant the FAIO. In most cases, the Division’s best targeting warrant runs the targeting working group and board, which may be less important for a unit that plans to principally use the dynamic targeting process. Without increasing the capacity of the targeting assembly line and the talent in it, a dynamic approach to targeting has its limits.

Finally, where should the intelligence component of the targeting enterprise reside for dynamic targeting? Why would not the intelligence fusion cell and FAIO that generates targets be collocated with the JAGIC and COIC? ATP 2.01, Collection Management, makes clear the dynamic reallocation of collection assets is an operations function. Commanders and G-2s, however, continue to physically anchor this function in the ACE and under the purview of intelligence specialists and warrant officers, reinforcing an organizational design at odds with both intelligence doctrine and the approach they have taken to targeting.

What are the implications for air space management and fire support? The implications and distinctions for air space management and fire support platforms are less pronounced between the deliberate and dynamic targeting processes. The deliberate process seeks to maximize effectiveness or, more specifically, the effect on the target. In the deliberate targeting process, the airspace management, primary shooter, and munition loads on air and ground fire support platforms seek to achieve the optimal angle of attack and convene a marriage between the best strike platform and munition against the target.

Conversely, the dynamic targeting process sacrifices effectiveness for flexibility. It is the process of the imperfect or suboptimal targeting solutions --- attack angle, strike platform, munition, and/or assessment platform. This, however, is not to say one cannot prioritize effects against a specific target in the dynamic targeting process, which is often done through restrictive measures (e.g., ROZs) and usually at the expense of other dynamic targeting efforts. Dynamic targeting inherently drives one to standard munition loads for both ground and air strike platforms to increase flexibility. Finally, dynamic targeting decreases or eliminates the need for pre-planned CAS (Type 2 Control) and Air Interdiction sorites and depends on immediate CAS (e.g., E-CAS).

What approach should a Division take to targeting? Our doctrinal framework presents deliberate targeting as the default setting for the targeting processes. Neither Joint nor Army doctrine draws a clear distinction between the deliberate and dynamic processes and the time horizons associated with each one. Advancements in artificial intelligence-enabled collection mean dynamic targeting will become exponentially easier and unconstrained geographically. A paucity of friendly munitions, an increase in the number of potential enemy targets, and a requirement to integrate non-lethal capabilities into the kill chain against Russian and Chinese targets, however, will demand a more deliberate approach to targeting. Consequently, Divisions find themselves in a targeting halfway house. They take a deliberate approach to targeting, which they often lack the proficiency to realize, and almost uniformly transition to a dynamic process they remain unorganized to execute. A Division can take one of three approaches to target but they demand different organizational designs.

BG(R) Mark Odom is a former commander of the 75th Ranger Regiment and now serves as a Senior Mentor for the Mission Command Training Program.